Erasing unwanted memories is still the stuff of science fiction, but Weizmann Institute scientists have now managed to erase one type of memory in mice. In a study reported in Nature Neuroscience, they succeeded in shutting down a neuronal mechanism by which memories of fear are formed in the mouse brain. After the procedure, the mice resumed their earlier fearless behavior, "forgetting" they had previously been frightened.

This research may one day help extinguish traumatic memories in humans - for example, in people with post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. "The brain is good at creating new memories when these are associated with strong emotional experiences, such as intense pleasure or fear," says team leader Dr. Ofer Yizhar. "That's why it's easier to remember things you care about, be they good or bad; but it's also the reason that memories of traumatic experiences are often extremely long-lasting, predisposing people to PTSD."

In the study, postdoctoral fellows Dr. Oded Klavir (now an investigator at the University of Haifa) and Dr. Matthias Prigge, both from Yizhar's lab in the Neurobiology Department, together with departmental colleague Prof. Rony Paz and graduate student Ayelet Sarel, examined the communication between two brain regions: the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex. The amygdala plays a central role in controlling emotions, whereas the prefrontal cortex is mostly responsible for cognitive functions and storing long-term memories. Previous studies had suggested that the interactions between these two brain regions contribute to the formation and storage of aversive memories, and that these interactions are compromised in PTSD; but the exact mechanisms behind these processes were unknown.

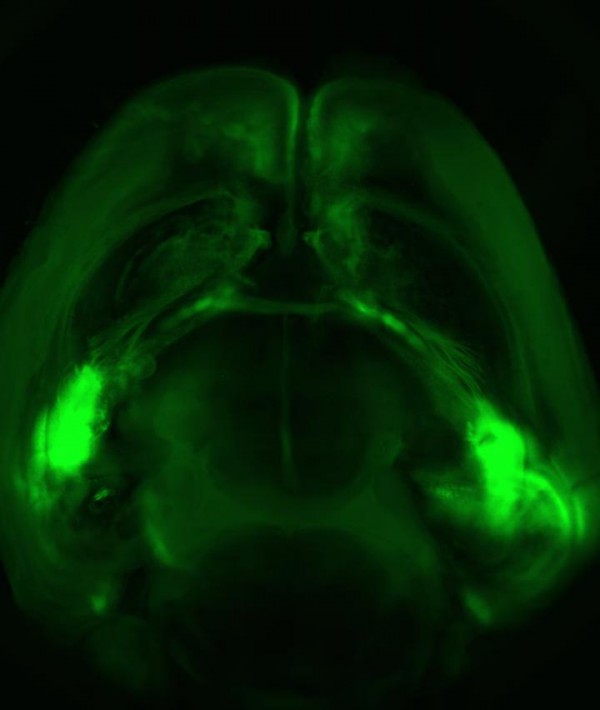

In the new study, the researchers first used a genetically-engineered virus to mark those amygdala neurons that communicate with the prefrontal cortex. Next, using another virus, they inserted a gene encoding a light-sensitive protein into these neurons. When they shone a light on the brain, only the neurons containing the light-sensitive proteins became activated. These manipulations, belonging to optogenetics - a technique extensively studied in Yizhar's lab - enabled the researchers to activate only those amygdala neurons that interact with the cortex, and then to map out the cortical neurons that receive input from these light-sensitive neurons.

Once they had achieved this precise control over the cellular interactions in the brain, they turned to exploring behavior: Mice that are less fearful are more likely to venture farther than others. They found that when the mice were exposed to fear-inducing stimuli, a powerful line of communication was activated between the amygdala and the cortex. The mice whose brains displayed such communication were more likely to retain a memory of the fear, acting frightened every time they heard the sound that had previously been accompanied by the fear-inducing stimuli. Finally, to clarify how this line of communication contributes to the formation and stability of memory, the scientists developed an innovative optogenetic technique for weakening the connection between the amygdala and the cortex, using a series of repeated light pulses. Indeed, once the connection was weakened, the mice no longer displayed fear upon hearing the sound. Evidently, "tuning down" the input from the amygdala to the cortex had destabilized or perhaps even destroyed their memory of fear.

Says Yizhar: "Our research has focused on a fundamental question in neuroscience: How does the brain integrate emotion into memory? But one day our findings may help develop better therapies targeting the connections between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, in order to alleviate the symptoms of fear and anxiety disorders."