Tokyo, Japan - Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University studied the neural response of Japanese junior high school students learning English as a second language, while listening to English sentences. More proficient boys showed more activation in parts of the brain associated with grammatical rules (syntax); girls used a wider range of language information, including speech sounds (phonology) and meaning of words and sentences (semantics). These discoveries may help optimize how boys and girls are taught English.

Children learn their native language with enviable ease and speed, but learning a second language is a far more varied process; though there has been much research into how the brain deals with new languages, we still don't know how variations in gender, age etc. specifically affect how we learn a new tongue.

A team led by Prof. Fumitaka Homae studied a rarely targeted population for this subject: Japanese junior high school students learning English as a second language in a school environment. The majority of work into the neuroscience behind learning a second language is based on immigrant populations in the United States, and children in the multi-lingual environment of Europe.

The boys and girls were given a standardized English test and a test of "Working Memory", a temporary storage in the brain used to organize, manipulate and analyze newly arrived information. They then listened to English sentences, including some with grammatical errors; observations of brain activity were taken using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and event-related potential (ERP) measurements. fNIRS tells us which parts of the brain are active; ERP gives us an idea of how brain activity varies with time.

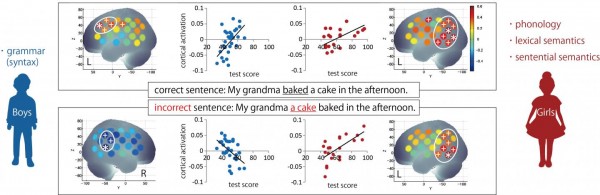

The results revealed a surprising disparity in how boys and girls deal with sentences. The girls performed better on the tests, and had more working memory. However, boys showed no correlation between working memory and performance, while girls did. Looking at brain activity, fNIRS revealed that boys showed increased activation with proficiency in the front of the brain when they heard a correct sentence, while girls showed more at the back. The front is linked with "syntactic" processing i.e. rule-based understanding of sentences; the back is associated with a wider range of language processing. Interestingly, boys displayed an overall decreased response for incorrect sentences; girls showed the exact opposite.

ERPs also showed disparities, with boys exhibiting a strong response to incorrect sentences from an early time, a phase thought to be associated with "syntactic" processing. Girls only showed a difference between correct and incorrect sentences at later times.

The emerging picture is of two different strategies to cope with a second language. Boys leverage efficient processing and rule-based "implicit" thinking; girls draw on a wider range of linguistic information, achieving "explicit" comprehension of sentences. A cursory look at test scores may have simply pointed to girls being "better" at learning English, but the mechanisms tell a far more interesting story.

A clearer picture of how boys and girls learn a second language (in this case, English) has the potential to revolutionize teaching in schools, building methods and syllabi to address directly strengths and weaknesses for both boys and girls.

This work was supported by two MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, "Integrative Research toward Elucidation of Generative Brain Systems for Individuality" and "The Science of Personalized Value Development through Adolescence: Integration of Brain, Real-world, and Life-Course Approaches". This project is part of work carried out at the Language, Brain and Genetics Research Center in Tokyo Metropolitan University. The manuscript reporting this finding has been published online in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.