Using advanced imaging, researchers have uncovered new information regarding traumatic microbleeds, which appear as small, dark lesions on MRI scans after head injury but are typically too small to be detected on CT scans. The findings published in Brain suggest that traumatic microbleeds are a form of injury to brain blood vessels and may predict worse outcomes. The study was conducted in part by scientists at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), part of the National Institutes of Health.

"Traumatic microbleeds may represent injury to blood vessels that occur following even minor head injury," said Lawrence Latour, Ph.D., NINDS researcher and senior author of the study. "While we know that damage to brain cells can be devastating, the exact impact of this vascular injury following head trauma is uncertain and requires further study."

This study, which involved researchers from Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, included 439 adults who experienced head injury and were treated in the emergency department. The subjects underwent MRI scans within 48 hours of injury, and again during four subsequent visits. Participants also completed behavioral and outcome questionnaires.

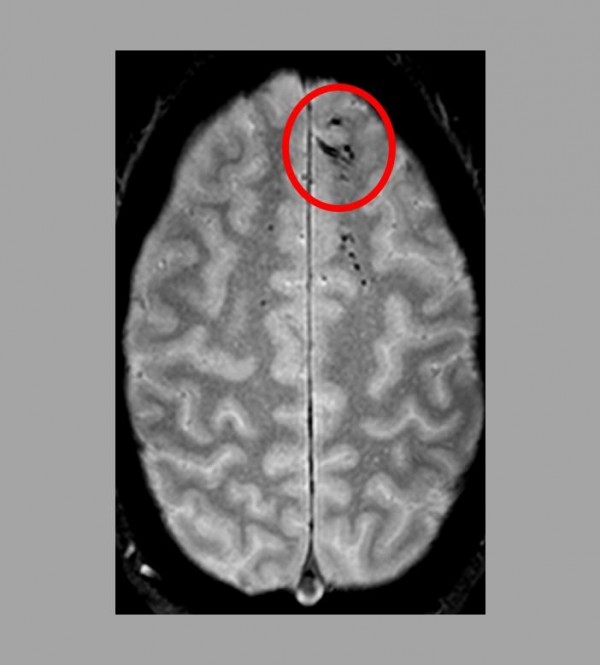

The results showed that 31% of all study participants had evidence of microbleeds on their brain scans. More than half (58%) of participants with severe head injury showed microbleeds as did 27% of mild cases. The microbleeds appeared as either linear streaks or dotted, also referred to as punctate, lesions. The majority of patients who exhibited microbleeds had both types. The findings also revealed that the frontal lobes were the brain region most likely to show microbleeds.

The patients with microbleeds were more likely to have a greater level of disability compared to patients without microbleeds. Disability was determined by a commonly used outcome scale.

The family of a participant who died following completion of the study donated the brain for further analysis. Dr. Latour's team imaged the brain with a more powerful MRI scanner and conducted detailed histological analysis, allowing the pathology underlying the traumatic microbleeds to be better described. The results showed iron, indicating blood, in macrophages (the brain's immune cells) tracking along the vessels seen on the initial MRI as well as in extended areas beyond that seen on MRI.

"Combining these technologies and methods allowed us to get a much more detailed look at microbleed structure and get a better sense of just how extensive they are," said Allison Griffin, a graduate student and first author of the paper.

The authors note that microbleeds following brain injury may be a potential biomarker for identifying which patients may be candidates for treatments that target vascular injury.