Screening the whole population of women in order to find those carrying mutated BRCA genes is a "questionable" idea because it would not improve outcomes, according to an opinion article in the journal JAMA Oncology.

The essay was written by Patricia Ganz, MD, director of cancer research at the Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA, and Elisa Long, PhD, assistant professor at the Anderson School of Management at UCLA.

For every 10,000 women who are screened, they calculated that BRCA testing would prevent four cases of breast cancer and two cases of ovarian cancer, when compared to testing based on whether the woman has a family history of cancer. This universal BRCA screening would extend patients' lives by an average of only 2 days, they added.

"The cost of BRCA testing would need to drop by 90% for testing to be cost-effective for the whole population," Dr. Ganz said. "Even though a very small percentage of women would benefit from universal BRCA testing, at $2,000 to $4,000 per test, such a strategy is an inefficient use of health care resources."

"If only 1 in 400 women across the country have one or both of the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutations, universal screening would cost $1 million to $2 million to detect a single BRCA mutation, or nearly $400 billion to screen all women in the US," Dr. Long told Medical News Today.

Dr. Long told Medical News Today that she carries the genetic mutation and could have benefitted from universal screening. "But as a health services researcher, I must also consider the relative value of different medical interventions," she added. If the cost for screening were to come down a great deal, it could be economically feasible, she added.

For the 99.75% who got a negative result on the genetic test, it would no increase in life expectancy, according to the authors. Universal screening could provide false reassurance and it would not eliminate the need for regular mammograms.

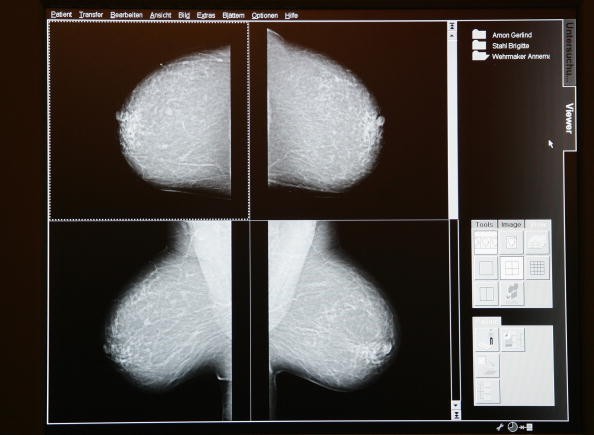

BRCA gene mutations are involved in 5% to 10% of the 233,000 cases of breast cancers that are diagnosed annually in the United States. Cases involving BRCA mutations usually develop at a younger age, often develop in both breasts, and are frequently a more aggressive subtype of breast cancer.

Currently, BRCA genetic testing is recommended only for women with a known family history of breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer, according to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The most commonly used BRCA genetic test is the Myriad test. Dr. Long told Medical News Today that she carries the genetic mutation and could have benefitted from universal screening. "But as a health services researcher, I must also consider the relative value of different medical interventions," she added.