The eggs of some butterfly and moth species vary to give females control over the paternity of their offspring, according to new research published today.

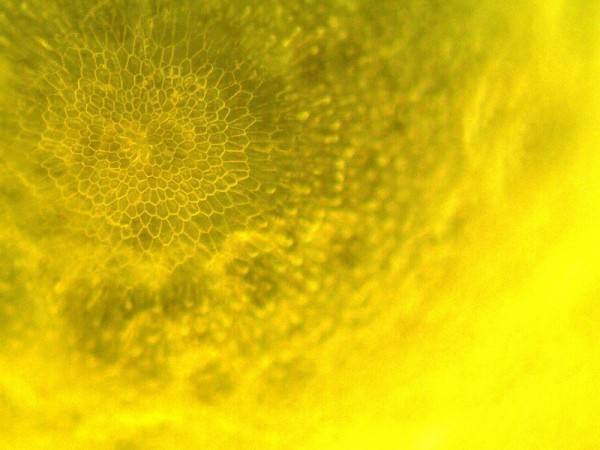

The new study reveals for the first time that the number and location of micropyles (small openings in the outer surface of a female insect's eggs which allow sperm to enter) are driven by a degree of female promiscuity.

The researchers behind the study, based at the University of Lincoln, UK, suggest that an increased number of micropyles enables the female butterfly or moth greater control over fertilisation.

The study is published today (Wednesday 21st December 2016) in the Royal Society's scientific journal, Biology Letters.

"Our study, rather intriguingly, raises the possibility that promiscuous female moths and butterflies can choose which male fertilises their eggs," explained Dr Graziella Iossa from the University of Lincoln's School of Life Sciences, who led the study. "In the group of insects we studied, sperm from several different males may enter the egg via multiple micropyles but only one fuses with the female pronucleus - in a process called physiological polyspermy. This process facilitates the possibility of mate choice within an egg cell. Such a mechanism could be akin to that observed in the comb jelly (Beroe ovata), where the female pronucleus moves among the different sperm cells before combining with one. We therefore concluded that the presence of multiple micropyles increases the opportunity for post-copulatory choice about which sperm fertilises the egg.

"This is the first study to show that micropylar variation is driven by female promiscuity - the more micropyles her eggs have, the more choice she is likely to have over which male fathers her offspring."

In most insects, sperm fertilise the egg via micropyles but despite having this one primary function, there is a considerable and unexplained variation in the location, arrangement and number of micropyles within and between species. Until now few scientists have attempted to seek a functional explanation for these differences.

This is the first study of its kind and it furthers our understanding of the relationship between female mating patterns and the number of micropyles in her eggs.

The team of researchers also included Dr Paul Eady from Lincoln's School of Life Sciences and Professor Matthew Gage from the University of East Anglia. Together they examined the eggs of 56 species from different families of butterflies and moths, whose number of micropyles varied from one to 15.

The research also considers that an increased number of micropyles in the surface of an egg could represent a bet-hedging strategy for a female butterfly or moth where sperm numbers are limited, for example when competition is high.

The full paper is available to view online.